|

| Lydia Davis [Paris Review] |

from Lydia Davis's Collected Stories:

Our Kindness

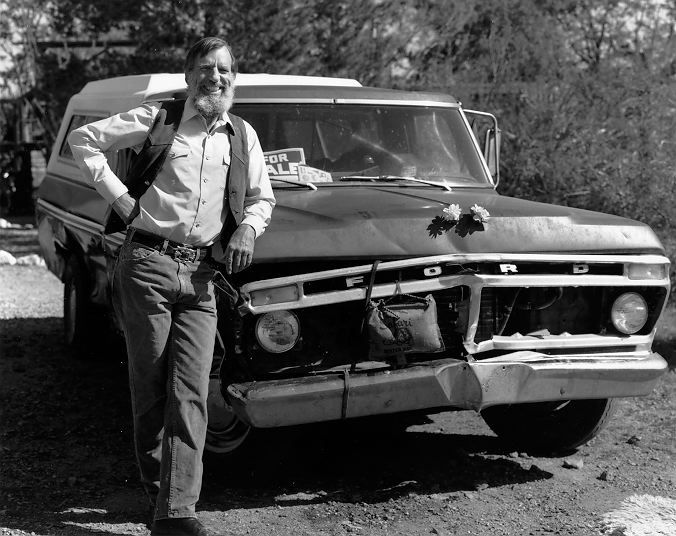

We have ideals of being very kind to everyone in the world. But then we are very unkind to our own husband, the person who is closest at hand to us. But then we think he is preventing us from being kind to everyone else in the world. Because he does not want us to know those other people, we think! He would prefer us to stay here in our own house. He says the car is old. We know that really he would prefer us to be acquainted with only a small number of people in the world, as he is. But what he says is that the car would not take us very far. We know he would prefer us to look after our own house and our own family. Our house is not clean, not completely clean. Our family is not completely clean. We think the car would serve us well enough. But he thinks we may want to go out and be kind to other people only because we would prefer not to be at home, because we would prefer not to have to be kind only to these three people, of all the people in the world the hardest three for us, though we can easily be kind to so many other people, such as those we meet in stores, where we go because there our car, he says, may safely take us.