kill a mother, birth motherless sons

absence of reason, dumb despair, bitter smell of death

a residential street, a sunny day

|

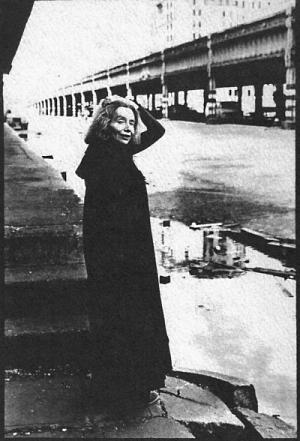

| Susan Howe [pic by Lawrence Schwartzwald] |

15

The

audience applauded

I

was welcomed as one returned from the grave.

My

imposter stood up

Her

speech was — forests, chasms, cataracts —

I

replied — Yes, I had been there —

slept

with the children every night —

wherever

I went — I went when I was sleeping —

All

eyes turned on me.

“Liar

— Have you seen the Lake of the North?”

she

said.

“Have

you seen the wreck of a ship?

— and

your scalp?

— How

did you cross the Great Camped Present?”

My

assurance failed

Welcomed

to the rock of my banishment

I

couldn’t utter a word.

Silence

resumed its wild entanglement

Thought

resumed its rigid courtesy.

20

.

. .

On

Monday, massacre, burning, and pillage

On

Tuesday, gifts and visits among friends

Warriors

wait

hidden

in the fierce hearts of children.

21

.

. .

Haunted

by the thought, the thread we hang on will save us

I

bit off and burned my fingers to keep from freezing.

. . .

. . .

I

the Fly

come

from Brighten

hook

storm

seawave

and salmon

Glass

house

Captain

Barefoot

gullet

of hook

all

sky

. . .

. . .

Nelson

wore a wig

and

after battle handed it to his valet

to

have the bullets combed out.

|

| T. Zachary Cotler [pic courtesy of The Poetry Foundation] |

from T. Zachary Cotler’s Sonnets to the Humans, 2013:

[p8]

Then

did you build this gallows,

calling

it a natural cause,

consenting

to abandon breath,

belief,

and memory on it? Was

I

one night, with cognac,

under

the scaffold,

washing

the feet. Because

there

is no grace except

of

the thinnest

duration,

I, too, was

hanged,

but at a distant station,

and

grace has a half-life; grace

is

a state one stage

decayed

from perfection.

[p14]

And

yet, a weathervane vine might have grown

from

the mud of your chests on a road away

from

asylum to tell you a wind full of

I

could have protected you,

but

there is only blew

the clothing off

your

children, blew into their brains

a

knowledge: not

because

an

icon is a closed gate to its promise,

but

because it is an open gate to Silence,

this

is why they ran

after

their flying shirts and hair

toward

a smoking Baal,

trampling

lightning-forked flowers,

terrified

of nothing.

[p20]

If

I stood for you, you stopped

alone

on a road by an ocean

with

bone ash blown back

on

your face — I’d thrown

an

urn. Anemones

pulsated:

atrium, carnation,

ventricle,

anus

of icon

of

Kali

— I’d thought

I

was on your knees in the tide

that

will cover the road, I down

without

devotion, having thrown

what

you’ve come to throw and now

with

some time to study the end

of

my time in you.