Venus

Anadyomene

As

from a green zinc coffin, a woman’s

Head

with brown hair heavily pomaded

Emerges

slowly and stupidly from an old bathtub,

With

bald patches rather badly hidden;

Then

the fat gray neck, broad shoulder-blades

Sticking

out; a short back which curves in and bulges,

Then

the roundness of the buttocks seems to take off;

The

fat under the skin appears in slabs:

The

spine is a bit red; and the whole thing has a smell

Strangely

horrible; you notice especially

Odd

details you’d have to see with a magnifying glass . . .

The

buttocks bear two engraved words: CLARA VENUS;

— And

that whole body moves and extends its broad rump

Hideously

beautiful with an ulcer on the anus.

from

Novel

Night

in June! Seventeen years old! — We are overcome by it all.

The

sap is champagne and goes to our head . . .

We

talked a lot and feel a kiss on our lips

Trembling

there like a small insect . . .

III

Our

wild heart moves through novels like Robinsoe Crusoe,

— When,

in the light of a pale street lamp,

A

girl goes by attractive and charming

Under

the shadow of her father’s terrible collar . . .

A

Dream for Winter

To

††† Her

In

the winter, we will leave in a small pink railway carriage

With

blue cushions.

We

will be comfortable. A nest of mad kisses lies

In

each soft corner.

You

will close your eyes, in order not to see, through the glass,

The

evening shadows making faces,

Those

snarling monstrosities, a populace

Of

black demons and black wolves.

Then

you will feel your cheek scratched . . .

A

little kiss, like a mad spider,

Will

run around your neck . . .

And

you will say to me: “Get it!”, as you bend your neck;

— And

we will take a long time to find that creature

—

Which travels a great deal . . .

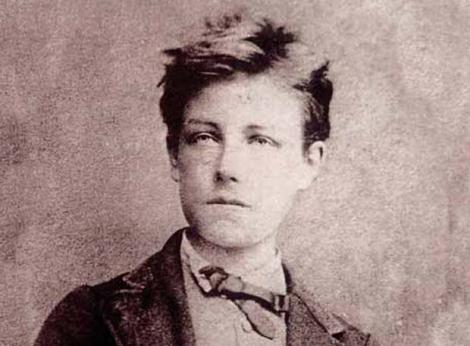

Seven-year-old

Poets

And

the Mother, closing the exercise book,

Went

off satisfied and very proud, without seeing,

In

the blue eyes and under his brow covered with bumps

The

soul of her child given over to repugnance.

All

day he sweated obedience; very

Intelligent;

yet dark twitchings, a few traits,

Seemed

to testify in him to bitter hypocrisy.

In

the shadow of the corridors with their moldy hangings,

Passing

through he stuck out his tongue, his two fists

In

his groin, and in his closed eyes saw spots.

A

door opened on to evening: by the lamp

You

saw him up there moaning on the stairway,

Under

a flood of daylight falling from the roof. In summer

Especially,

overcome, stupefied he was bent

On

shutting himself up in the coolness of the outhouse:

There

he meditated, peacefully, opening his nostrils.

When

washed from the day’s odors, the small garden

Behind

the house, in winter, lit up with the moon,

As

he lay at the foot of a wall, buried in clay,

And

rubbed his dizzy eyes to bring about visions,

He

listened to the mangy espaliers as they seemed to swarm.

Pity!

only those children were his friends

Who,

sickly, bare-headed, with eyes weeping on their cheeks,

Hiding

thin fingers yellow and black with mud

Under

worn-out clothes stinking of diarrhea and old,

Talked

with the gentleness of idiots!

And

if she caught him in actions of filthy pity,

His

mother was horrified. The deep tenderness

Of

the child forced itself on her surprise.

That

was appropriate. She had the blue glance, — that lies!

At

seven, he wrote novels about life

In

the great desert, where exiled Freedom shines,

Forests,

suns, rios, plains! — He was helped

With

illustrated newspapers where, blushing, he saw

Spanish

and Italian girls laugh.

When

the daughter of the workers next door came,

— Eight

years old, — brown eyes, wild, in a calico dress,

The

little brute, and when in a corner,

She

had jumped on his back, shaking her long hair,

And

he was under her, he bit her buttocks,

For

she never wore panties;

— And,

bruised by her fists and heels,

Took

back the taste of her flesh to his room.

He

feared the grey December Sundays,

When,

his hair greased, on a mahogany stool,

He

read a Bible with cabbage-green edges.

Dreams

oppressed him every night in his small room.

He

did not love God; but the men whom, in the brown evening,

Swarthy,

in jackets, he saw going home to their quarters,

Where

town criers, with three drum rolls

Make

the crowds laugh and roar over edicts.

— He

dreamed of an amorous pasture, where shining

Swells,

natural perfumes, golden puberties

Move

calmly and take flight!

And

as he especially savored dark things,

When,

in his bare room with closed shutters,

High

and blue, sourly covered with humidity,

He

read his ceaselessly meditated novel,

Full

of heavy ocherous skies and soaked forests,

Of

fresh flowers opened in the astral woods,

Dizziness,

crumblings, routs and pity!

— While

the noise of the neighborhood went on

Down

below — alone, and lying on pieces of unbleached

Canvas,

and violently announcing a sail!

The

Hands of Jeanne-Marie

Jeanne-Marie

has strong hands,

Dark

hands the summer tanned,

Hands

pale like dead hands.

— Are

they the hands of Juana?

Did

they get their dark cream color

On

pools of voluptuousness?

Have

they dipped into moons

In

ponds of serenity?

Have

they drunk from barbaric skies,

Calm

on charming knees?

Have

they rolled cigars

Or

traded in diamonds?

On

the burning feet of Madonnas

Have

they tossed golden flowers?

It

is the black blood of belladonnas

That

bursts and sleeps in their palms.

Are

they hands driving the diptera

With

which the blueness of dawn

Buzzes,

toward the nectars?

Hands

decanting poisons?

Oh!

what Dream has held them

In

pandiculations?

An

extraordinary dream of Asias,

Of

Khenghavars or Zions?

— These

hands have not sold oranges,

Nor

turned brown at the feet of the gods;

These

hands have not washed the diapers

Of

heavy babies without eyes.

(They

are not hands of a cousin

Or

of working women with large foreheads

Burned,

in woods stinking of a factory,

By

a sun drunk on tar)

They

are benders of backbones

Hands

that do no harm

More

fatal than machines,

Stronger

than a horse!

Stirring

like furnaces,

And

shaking off all their tremblings

Their

flesh sings Marseillaises

And

never Eleisons!

(They

would strangle your necks, o evil

Women,

they would crush your hands

Noblewomen,

your infamous hands

Full

of white and carmine

The

beauty of those loving hands

Turns

the heads of ewes!

On

their savory finger-joints

The

great sun places a ruby!)

A

stain of populace

Turns

them brown like a breast of yesterday:

The

back of these Hands are the places

Where

every proud Rebel kissed them!

They

have paled, marvelous,

Under

the great sun full of love

On

the bronze of machine-guns,

Throughout

insurgent Paris!

Ah!

sometimes, o sacred Hands,

At

your wrists, Hands where tremble our

Never

sobered lips,

Cries

out a chain of clear links!

And

it is a strange Tremor

In

our beings, when, at times

They

want to remove your sunburn, Hands of an angel,

By

making your fingers bleed!

Evening

Prayer

I

live seated, like an angel in the hands of a barber,

In

my fist a strongly fluted mug,

My

stomach and neck curved, a Gambier pipe

In

my teeth, under the air swollen with impalpable veils of smoke.

Like

the warm excrement of an old pigeonhouse,

A

Thousand Dreams gently burn inside me:

And

at moments my sad heart is like sap-wood

Which

the young dark gold of its sweating covers with blood.

Then,

when I have carefully swallowed my dreams,

I

turn, having drunk thirty or forty mugs,

And

collect myself, to relieve the bitter need:

Sweetly

as the Lord of the cedar and of hyssops,

I

piss toward the dark skies very high and very far,

With

the consent of the large heliotropes.

.jpg)