|

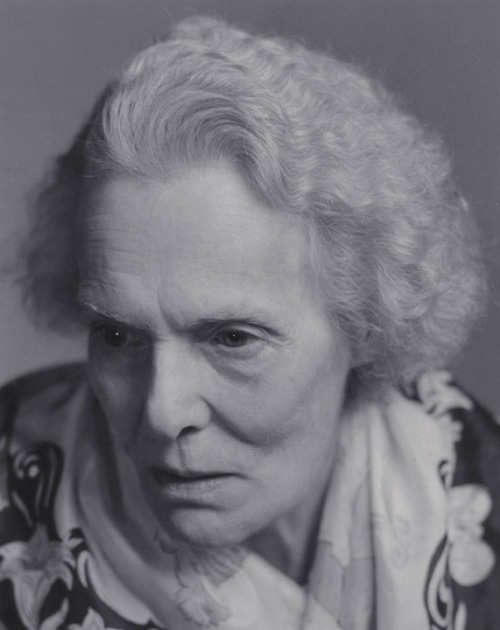

| Elise Cowen [Ahsahta Press] |

from Elise Cowen's Elise Cowen: Poems and Fragments, ed. Tony Trigilio:

A cockroach

Crept into

My shoe

He liked that fragrant dark

A cockroach

Climbed into

My shoe

Away from cold & light

I crept my hand

In

After him

Cockroach

The best I can do for you

Is compare you to bronze

And the Jews

You're not really welcome

to use my shoe

For a roadside rest

Obvious

From the shadow of my hand

You keep coming back

across my floor

For more? — look —

You've lost an antenna

I treat you

seriously affectionately as a child

——

And not to forget

the cockroach

that crawled across

the floor & painted

blue under the stove

somewhere in the [ ]

to God knows where

——

Keep out of the light

Out of the dangerous radiance of

Bong Eyes

Respect the cockroach centuries

And the heavy confection of plunder kitchen

——

Must I move to get away from killing you

And carry to Sutton Place in the back of my mind

back to San Francisco ants

To get away from you?

I know —

I'll starve a hungry cat

And name it Darwin

Angels

If I crawled into your crack in the wall

Four clumsy appendages, too dumb to talk

What would you & your dynasty do?

Tickle me to death under your indifferent feet

Teach me to be a makeshift cockroach

Live off my flesh & use the bones for cockroach walls

Cockroaches

Prepare

I'm coming in