|

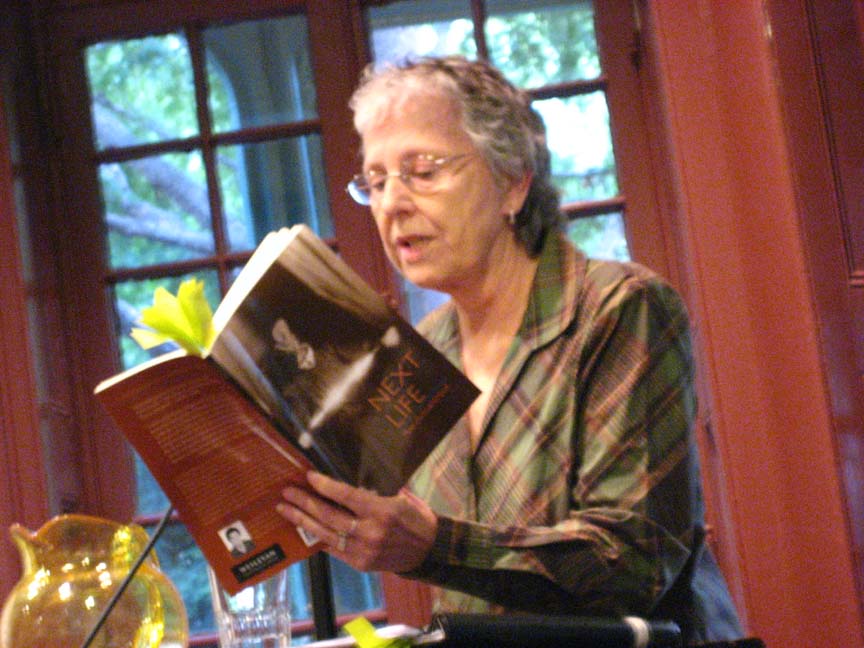

| Alice Notley [vimeo] |

Just Under Skin of Left Leg

a dark woman, Camelia Luna

who has Anna Akhmatova's nose

welcomes me to her basement floor dwelling —

I'll help her carry her dead father

I tie him to myself, by the neck . . .

"He must be heavy," she says. He

wakes up and mutters unmemorably.

We called Camelia Cammy (pronounced

Commy) when I was a kid

Virginia my former therapist called me "loony"

"loony poet" — "You were this loony poet."

—————

Heavy with the season. Don't want to give myself

to a new cycle of work and socializing.

Say something pretty: "Dorior, more golden than a door."

Anyone gets tired of carrying fathers.

In my dream Cammy's father

had been a Mafia don. She answered the door

in a blue tulle dress.

—————

"This poem needs your love."

An American might say that

how disgusting

Love an American: "they just love us."

Get some Housing Projects; listen to Rap in them;

turn rightwing electing a maskface in a nice suit;

explode some nuclear bombs.

Americans come to Paris to find out they're Americans

how interesting for them; I mean us

tired of carrying that, carrying that weight

around my neck, who the fuck is this man?

depicted as the weight of your life, can

he be the brunt the cruelty

of that? Yes I carry him, carry him . . .

—————

Out in the forest with an empty pickle jar

waiting to catch a pickle, no a pygmy owl, or

something like that!

if way beneath

my surface, I can find only a diatribe,

shouldn't you listen? Way . . . way below —

where the real story must be.

—————

Marguerite Yourcenar said

she wouldn't be in a book of women

collection of women's writings because

only women would read it, and

they already knew they were angry —

And

anger, she said, is one, one person

a little personal sputter.

But that's that kind of anger, Marguerite —

what about

an anger like Dante's, a whole leaden sky

a church-charged orthodox anger,

creating, in Amer-lingo, a norm for the Great?

That's not so bad, to damn in perpetuity,

if you're Great?

Well, she says,

it's certainly not trivial.

—————

I can't seem to get down into the caves

and the lovely pleasures of the pursuit of the Soul

by Will. What will happen, will I ever find me

in such a way that I'll change, off the page?

—————

I know where Dante might be —

tied round my, Camelia Luna's neck.

"What did he say when he spoke?"

Who cares?

The weight round my neck should die.

—————

'Hi, Mitch.' 'Hi.

Catch anything in that jar?'

'A dead man's ass disguised as light.'

'Aren't you being hard on D? He's like me'

'And me —'

First to the left, then to the right —

No, left, all the way to the left

Take it as far as you can.

—————

Walking with my toes curled as if I were in orgasm;

now look up at the strange sky above soft trees.

I don't want to create any meaning;

I want to kill it . . .

You made meaning; I'm

trying to make life stand still,

long enough so I can exist.

I, truly, am speaking