a gold, late-model Grand Marquis, remember those?

The driver's keys, unclutched, on the seat

beside him, a little of his youth

still hesitant on his face,

his skin so blue —

the late afternoon fading as well in the early-summer's

heat, the car's hazard lights

blinking on-and-off, on-

and-off, relaying a last-minute

presence of mind —

and then doubt —

courage, and then a failing.

Hard to know

whether he was coming or going — in a real flap

or taking his own sweet time —

the back seat crammed with a vintage red

vacuum, broken lamp, and barrage of cardboard boxes

holding God-knows-what,

the sum total of a kind of living.

A passerby laughed with me about that.

We took turns leaning into the car's open windows

and shouting into the man's face.

That can sometimes be a life-saver;

even wrong-sounding words

better than a roaring white street

of silence.

For some reason I thought

to recite a few poems

that might awaken a man;

one by Carver about the last years

being "pure gravy,"

and a few words from John Donne

on the subject of death being not especially "proud" . . .

while my cohort, curious as I was

to see some trick of transparency — a lifting up,

or out of, as easy to believe

as smoke from a winter chimney —

kept repeating, "Can you hear me? Are you

diabetic?" and once, just for a joke,

"Hey buddy, here come the police!"

But there were no sirens,

although we'd called for response;

the air hung heavily in the street, and the man

didn't even twitch, not once,

while we yodelled and felt ill-at-ease;

a third bystander soon

sprinting to the nearby Big-B Saloon

where the girls would start dancing, later,

to spread the news, some sorry sod

blacked-out — maybe not even breathing —

Another quarter-hour tripped by

like soft, sullen eternity,

an ambulance finally gliding into view —

it seemed cruel providence

to remember the milk I'd bought, spoiled in the heat.

"You did the right thing,"

the paramedic said, pulling on his baby-blue latex gloves;

although I'd been afraid

to touch a man with writhing-snake tattoos,

his mouth gaping —

had offered only badly-canted verse

as resuscitation.

"He's a known drug-user; has OD'd before,"

the medic said, without blame,

as if despair were an accepted fact

like the earth being round

and wobbling slightly on its axis.

We were standing in front of the Bellevue,

a roughneck hotel survived

from boom-and-bust days in a once-shake-mill town —

cars slowing, faces craned

to catch sight of someone

unrecognized, and in real trouble —

that's as good as it gets; a thrilling

of blood, their own lives

remarkably unscathed —

Maybe they thought I knew

the collapsed man, had chosen

to love him, the way we do — helplessly,

and half-hearted —

or cheapened the story

once they got home, some drifter's

girlfriend or sister, bawling her eyes out

on the main drag, they saw the whole thing.

I hate that, people blowing things

out of proportion. It shows us up

to be only passing strangers, nothing more.

Believe me, it was this simple.

I saw the gold car, the blued skin

of the man inside,

and how he wanted

to prepare for beauty,

give it his best shot,

get somewhere without any hitches, for once —

without that shimmering hook, or hoop

that always snared him —

and such a quiet approach

on old, bald tires.

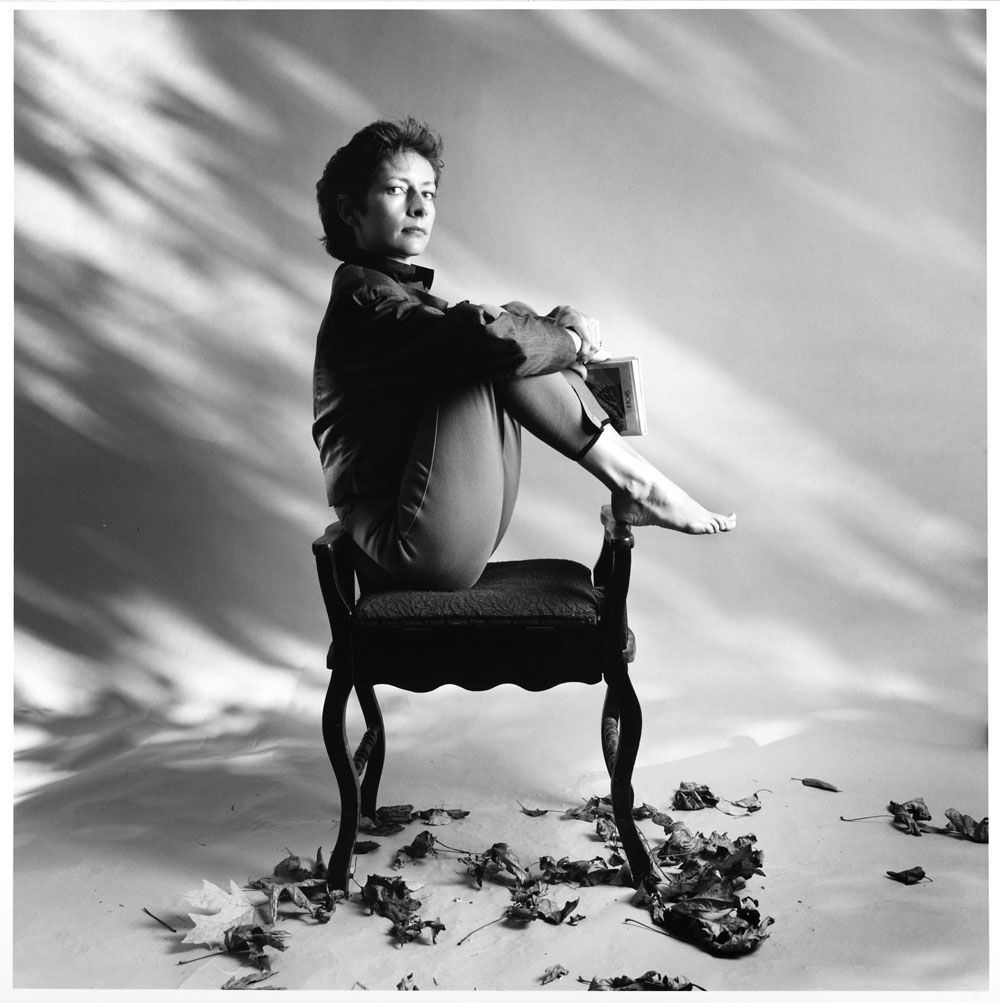

I keep coming back to admire this work. I am really envious of this skilled poet. A wonderful poem.

ReplyDelete