|

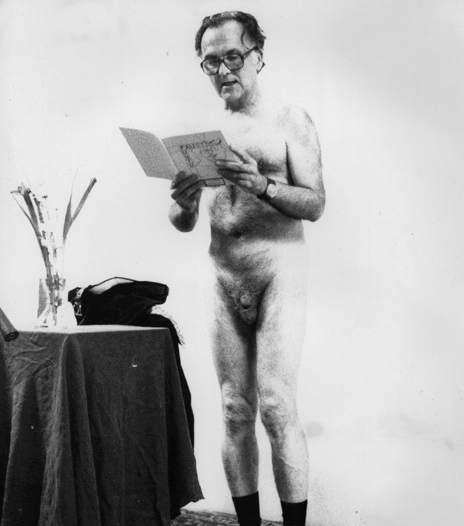

| Robert Duncan [Mark I Chester] |

from Robert Duncan’s The H D. Book (The Collected Writings of Robert Duncan):

“What

should he read — ” her paramour asked as we walked toward the

campus the day of our first meeting — “Should he read Eliot?”

“No,” she made her pronouncement, speaking of me in the third

person — it was as if he had enquired on my behalf at Delphi of the

oracle: “His work is too melodramatic as it is. He should read

Pound.”

Just

here, with this memory, a third scene, I had the sense of a missing

element of my story coming into the picture. It was at once the

weakest in its claim to being a living reality — just as the claim

of a stylish mode in itself can seem a weak ground indeed. But the

reality of art was to be for me always a matter of love and

taste, Eros and Form. Had that

arbiter not been so purely a creature of taste or fashion, of an even

snobbish sense of what was right,

and so little — it was my entire impression of her — a creature

of soul, I might have

mistaken taste for liking. Liking, being fond of like things and

people, was itself a mimic of love, and could be then a mimic too of

judgment. But taste — even the snob’s presumption — excited in

me another apprehension, the lure of a quality in a work in itself

that demanded something of me, beyond the recognition of my own

feelings expressed in an artist’s work, the recognition of feelings

that were demanded by the form of the work itself. Love and the sense

of Form and Judgment — passion and law — know nothing of liking

or disliking. The modern taste, the exacting predilection, beyond

likes, was, just here, a third aspect — my involvement with

the structural drama of H. D.’s art. I was as a poet to be not only

a Romantic but also a Formalist.

Form

is the mode of the spirit, as Romance is the mode of the soul. In

liking and disliking there was a beginning of creating one’s soul

life, determining in recognizing what would be kindred and what alien

to one’s inner feeling of things, making a likeness of one’s self

in which the person would develop. In taste, almost the vanity of

taste, there were intimations of the formal demand the spirit would

make to shape all matter to its energies, to tune the world about it

to the mode of an imagined music.

In

my conversion to Poetry I was to find anew the world of Romance that

I had known in earliest childhood in fairy tale and daydream and in

the romantic fictions of the household in which I grew up. I had set

out upon a soul-journey in my falling in love with my teacher in

which she set me upon the quest of the spirit in Poetry, that

reappeared later disguised in this foolish, even vain, presentation

of a lady of fashionable tastes who demanded of me the secret of form

hidden in the modernist style. The high adventure was to be for me

the romance of forms, haunted by its own course, its own secret

unfolding form, relating to some great form of many phases to which

it belonged. The crux of my work was still to be melodramatic — if

we remember the meaning of that word as being “a stage play

(usually romantic and sensational in plot and incident) in which

songs are interspersed, and in which action is accompanied by

orchestral music.” But the elements of stage and play, of romance

and sensation, that are usually taken to belong to the psyche-drama,

were to come more and more to be seen to belong to, to illustrate and

accompany the musical structure. So the world of the spirit hidden in

the experience of soul and body becomes dominant, informing romance

and sensation with a third possibility, even as soul dramatizes or

enacts body and spirit, or as body incarnates as a living idea

propositions of spirit and soul. The orchestration no longer

accompanies but leads the dance. . . .

Where truth is the root of the art, to come to fullness means to let bloom the full flower of what one was, the truth of what one felt and thought — a flowering of corruptions and rage, of bile and intestines, as well as of sense and light, of glands and growth. For it was not the ideal or the model of feeling that I saw as my work, but the revelation of the nature of Man in my own being. . . .

I was to undertake the work in poetry to find out — what I least knew myself — what I felt at heart. But in the beginning the work was a gift to my teacher. I was to undertake the work to present what I felt at heart to someone who had a trust I did not have in the heart, who wished for just that gift for love's sake. I was to undertake the work in order that Eros be kept over me a Master. . . .

Books were the bodies of thought and feeling that could not otherwise be shared.

Where truth is the root of the art, to come to fullness means to let bloom the full flower of what one was, the truth of what one felt and thought — a flowering of corruptions and rage, of bile and intestines, as well as of sense and light, of glands and growth. For it was not the ideal or the model of feeling that I saw as my work, but the revelation of the nature of Man in my own being. . . .

I was to undertake the work in poetry to find out — what I least knew myself — what I felt at heart. But in the beginning the work was a gift to my teacher. I was to undertake the work to present what I felt at heart to someone who had a trust I did not have in the heart, who wished for just that gift for love's sake. I was to undertake the work in order that Eros be kept over me a Master. . . .

Books were the bodies of thought and feeling that could not otherwise be shared.

No comments:

Post a Comment