|

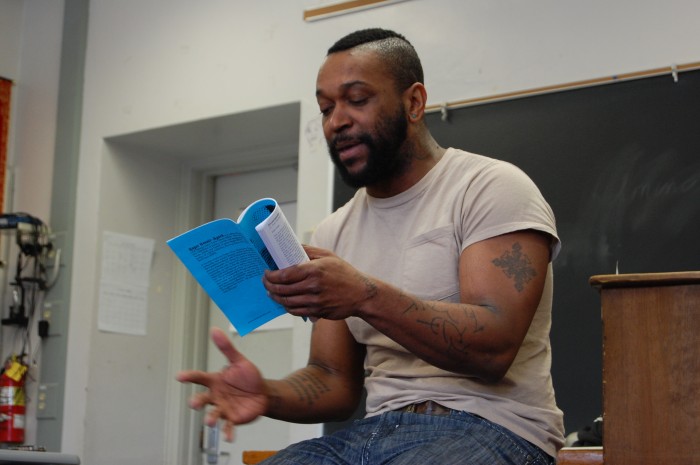

| Roger Bonair-Agard [thecommunicator online] |

from Roger Bonair-Agard's Bury My Clothes:

In 2010, an entirely black penguin was discovered in Antarctica.

The genetic possibility of an all-black or all-white penguin is only

miniscule. The following is taken verbatim from a Reuters news

report covering the discovery:

"An all-black penguin has been discovered in Antartica. It seems

to be

assimilating nicely and has even found itself a black & white mate . . .

Recently discovered all-black penguin seems unafraid to defy

convention. . . .

Biologists say that the animal has lost control of its pigmentation.

Other than [that] the animal appears to be perfectly healthy. 'Look

at the size of those legs,' said one scientist. 'It's an absolute monster.'"

The all-back penguin speaks

17 facts you did not know about me

1. I was born here, raised here, met my mate and warmed my

eggs — here.

2. Fully ten seasons passed before you noticed me. Don't make up

theories now,

Johnny-come-lately.

3. Penguins are color blind.

4. Fuck your bell curve, motherfucker — I know that's not a

fact. It's an imperative.

5. Penguins deliberately don't read so we wouldn't have to learn

words like assimilate, like discriminate, like mutate.

6. We pray every day. It's a simple chant:

Evolve, Evolve, Evolve

7. Can't you see it's getting warmer? Don't you see the ice melting?

8. I know the word rhetorical, bitch

9. I'm actually the same size as all the other penguins.

10. You suffer from ocular negrophobia, the condition in which all

black (all-black?) things look really large and scary. Yes, I

know that's a fact about you, motherfucker.

11. I hate you.

12. I don't believe in the same God as you.

13. Evolve, Evolve, Evolve

14. There are two other all-blacks. We do not know each other.

15. I'm prettier than you.

16. I'm making up a song about you. It's called "Albino Mother-

fucker."

17. We have a few all-white penguins here. We're cool. They hate

you too.

In the year of the cutlass

The cocoa hung low and golden

in the cool dark of the Tamana forests.

That year, I was taught

the specific English of the brushing cutlass;

the high arc you made with the long handle

down in front of your left foot, the perpendicular

blade scything the brush into tiny green

tatters of rain with each deft rotation.

In the year of the cutlass, I learned

how to tell if the cocoa was ripe and where

to look for a snake in the branches,

for it was also the year of the mapepire,

the year of the coral and the year I first

noticed the cane being fired. I was taught

the cutlass would go straight through the thickest

cane if you cut down at an angle, in the shaft

on the bias and not at the tree's sweet joints.

I was taught the cutlass was a small spade

for turning the damp brown dirt to throw

seeds in, and then it could become

the year of tomatoes on the vine, the year

of pigeon peas and the year of the chive.

My wrists became cabled and I could

trim the hedge bushes that year. I straightened

the ixoras and the hibiscus

with practiced, precise swings

that launched bits of branch and leaf.

I edged the lawn, needing

neither string to measure a level line

nor shoes to protect my feet.

It was the year of feeling sweat

and feeling my body bristle

like a horse's when the girls passed.

I learned the beautiful song

of the blade when it caught the occasional stone

and sparked shock up my arm. I learned

to aria with the blade's notes then,

how to sing in time,

every swing a metronome.

It was the year of the baritone,

year of the African sanctus and the negro

spiritual. It was the year my grandfather gave me

my own, its handle carved from cedar

with three rivets to hold the hard wood

steady against the steel. I learned

to let the water run the flat side down

the grooves in neat streams.

I learned you could threaten a man

with the cutlass and only beat him

with the flat-side; the year

of the plan-ass and the year I learned

that Choonie called the blade a pooyah

and the peyol from Lopinot sometimes

called it a machet. It was the year

of rum and ole talk. It was the year

of learning to insult your friends

and the year of garlic on the blade

to make the inflicted wound

unhealable. My father left

and my grandfather started telling secrets

about who would come to take the land.

It was the year of practicing

to use the cutlass like a sword. It was the

year of sharpening my body.

It was the year of listening

to the different ways the blade sang;

the year of its tenderness against a fowl's neck

and the year of body against body

in the hot sun — It was the year

of lashing bamboo to make a table,

a small lean-to, a bench. It was the year

people began to die; and my father left

with the sound of a pomerac tree falling.

I learned to keep the cutlass leaned

by the bed, because it was the year

of the bandit and the shape shift,

plant yourself deep to come back

as something new — to learn slowly

how to leave so the cut is quick,

bloodless, barely burning.

No comments:

Post a Comment